As geographers, Dr. Yair Grinberger and Professor Daniel Felsenstein love maps. But rather than perusing old, dusty maps of countries yore, or drawing up innovative and creative maps of the world today, their maps are fascinating exercises in asking “What if…?”

Dr. Grinberger and Prof. Felsenstein’s “map” is actually a computerized model of Israeli cities, based on real data taken from official, comprehensive databases. (Their data is on the level of buildings, not individual people). With a few clicks, they can insert an exogenous shock that affect cities – such as an earthquake, flood, or bomb – and map the outcomes. While the short-term effects and needs of such disasters are self-evident, the long-term effects are often more complex.

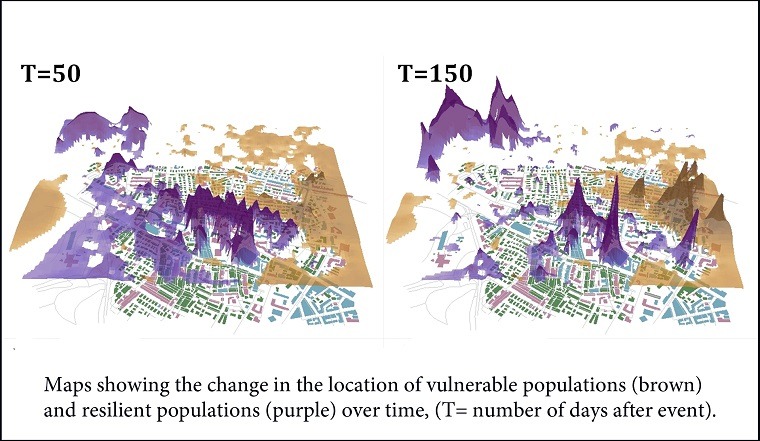

Their model, named DySTUrbD (Dynamic Simulation Tool for Urban Disasters), does exactly that: it looks 3 years into the future, examining how a city bounces back, or changes, in the aftermath of such a shock. Planners, engineers, budget officers, and first responders at the municipal and national levels can use the model to understand how short- and long-term policies may eventually affect building use, commercial activity, population distribution, transportation, productivity, and labor and housing markets – among others. (DySTUrbD is not a predictive tool).

"Our map helps policy-makers develop emergency systems, examine which options are most effective, and gain a different understanding of the city. Our model can significantly impact policy."

Dr. Yair Grinberger

Pandemic Meets City

As the Coronavirus spread, Dr. Grinberger and Prof. Felsenstein realized that DySTUrbD was not equipped to deal with this new urban crisis. With seed funding from the Ministry of Science and Technology, they began incorporating a classic epidemiological model that simulates the effects of contagion in cities – at the level of individual buildings. Known as SEIR, it tracks (S)usceptible, (E)xposed, (I)nfected, and (R)emoved (recovered or dead) populations.

When integrated into DySTUrbD, this “pandemic module” will generate a spatial-social model of contagion, and Dr. Grinberger and Prof. Felsenstein will be able to begin introducing policies, tweaking factors, and creating various outcomes 3 years down the line.

For example, they will be able to set their model to various pandemic scenarios and examine whether long-term impacts emerge, such as differences among populations (including welfare-related implications), which long-term impacts arise from different short-term policies, and identifying the conditions that make short- and long-term policies most effective.

"Our model is unique in that it explicitly addresses distributional questions: we ask who wins and who gains, in terms of different socio-economic groups. We’ve incorporated normative socioeconomic assumptions, which enables us to see how particular policies might affect poor and rich populations differently."

Prof. Daniel Felsenstein

Looking Forward to a Post-Coronavirus World

Looking forward, Dr. Grinberger and Prof. Felsenstein plan to finish incorporating the SEIR module by the end of 2020. They hope that their research will help decision-makers examine how varying degrees of intervention will play out, including determining whether to restrict the mobility of different populations and whether particular activities should be temporarily shut down. In addition, they can see how long-term policies, such as different forms of financial support to some/all of the population are likely to affect the future development of cities.

A Case Study: A Tale of Two Earthquake-Stricken Cities

In the pre-pandemic days, Dr. Grinberger and Prof. Felsenstein used DySTUrbD to compare how, if at all, an earthquake would differently affect Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Given the blockage of roads and widespread destruction, a few noteworthy changes took place. First, people became less mobile; in Jerusalem this led to an increase in neighborhood commerce and a decline in the centrality of the downtown area. In Tel Aviv, on the other hand, the market balanced itself out with less dramatic shifts.

In terms of housing, processes of gentrification were evident in Jerusalem. Higher-earning households were able to relocate more easily, even if this meant driving up the prices in lower-income areas and driving out the local population.

Understanding these domino-like shifts helps decision-makers understand the long-term effects of exogenous effects, creating better emergency plans that comprehensively address the needs of all the city’s residents.

Image (edited) courtesy of Yair Grinberger & Daniel Felsenstein, first published in Planning Support Systems and Smart Cities.